Why your horse almost certainly does not respect you

Debunking the dominance-leadership complex

This has been one of my most requested posts since I started The Equine Ethologist. I am often asked to debunk the pervasive idea that we need to gain our horses “respect” and become their “leaders” in order to interact with them in a safe and effective way. I will try to do that in this post. Fair warning - this is another long one.

In the horse world, the notion of respect is deeply intertwined with ideas of dominance and leadership, in ways that imply a causal relationship between them. We are taught from a very young age that our horses should “respect” us as their “leaders”, and that when they don’t, it is an expression of their innate desire to establish “dominance” over each other and over us. I call this unholy trinity the dominance-leadership complex.

If you have spent any time at all in the horse world, you will be familiar with it. It comes in different guises. You may have heard phrases such as “your horse is trying to take over” or “you need to show him who’s boss”. Sometimes, the words are softened to sound less war-like; you may have been told some variation of “your horse doesn’t respect you” or “you need to establish yourself as a leader”. These are all just different ways of expressing the same idea: that horses try to disrespect and dominate us at the earliest opportunity, and that we need to actively prevent that from happening.

This is complete nonsense, thoroughly debunked by science. Yet it is still used to justify horrendous physical and emotional abuse of horses through the use of force and coercion. Not only that, it obscures the truth of horse-human interactions behind a smokescreen of pseudoscience1 and misinformation, making it unnecessarily difficult for well-intentioned horse owners to relate to their horses in an evidence-based and compassionate way.

Challenging the dominance-leadership complex is a moral imperative for everyone involved with horses, but misinformation dies hard. There is still a lot of confusion and uncertainty around the topic of dominance and leadership in horses, aggravated by the fact that the concepts of “dominance” and “leadership” are defined very differently in ethological research compared to our lay understanding.

In this post, I will try clear up at least some of the confusion. I will define each of the concepts dominance, leadership, and respect in turn, explain how the ethological definition differs from the lay definition and explain what we currently know about how these three concepts manifest in horses. I will also give some practical guidance on what you can do to build a good relationship with your horse.

I hope this post will give you the confidence and arguments you need to go out there and help me bury the dominance-leadership complex for good, in an unmarked grave.

What is “dominance”?

Let’s start by taking a look at the lay definition that shapes our understanding of how dominance manifests in horse-human interactions. The Cambridge Dictionary defines dominance as “the quality of being more important, strong, or successful than anything else of the same type” as well as “the action of taking control of other people or animals in a forceful way, or the quality of liking to do this”. The vast majority of us think of some variation of this definition when speaking of “dominant” horses.

According to this definition, dominance is a qualitative assessment of personal characteristics, meaning that any individual who is dominant is also “important, strong, or successful”. By implication, whoever they are dominant over must be the opposite of these things, i.e. unimportant, weak, or a failure. In this dichotomy, every sane person would automatically prefer to be the dominant one, right? So if we believe that the horse-human relationship is a binary state where one party is dominant and one is submissive, it makes sense for us to want to be the dominant one - and to assume that our horses feel the same way. Being dominant, after all, is a reflection on our person.

This creates a relationship based on constant conflict, where horse and human fight each other for the dominant position. When viewed through this lense, any misbehaviour on the part of the horse will be perceived by the human as an intentional attempt to overthrow us and force us into the submissive position. This, in turn, makes it easy to justify using force to fight back in order to retain our position as the “important, strong, or successful” one.

But here’s the thing: horses don’t read the Cambridge Dictionary. Their understanding of the world is quite different from ours. Just because we humans engage in interpersonal scheming doesn’t mean every other species on the planet does, too. We have no reason to assume that horses enjoy picking fights with us, because that is not what they do to each other.

But wait, I hear you say. Ethologists speak of dominance too, right?

This is where the confusion around definitions comes in. We ethologists do indeed observe and record dominance interactions among the animals we study, but for us, “dominance” has a very different definition to the lay one we’ve just explored. By necessity, science borrows many words from everyday English to describe scientific concepts, but these are always defined in very narrow and specific ways that only have very weak connections to the lay definitions. A lot of confusion arises when people are unaware of this, or are unclear about or inconsistent in which definition they are referring to.

In ethology, dominance is generally defined as the relationship between two individuals that describes which individual in a pair will have primary access to a particular resource. This is a very important distinction. Dominance as used in behavioural research is not a qualitative assessment of the personal characteristics of an individual - i.e., a state of being “important, strong, or successful” - but a description of the outcome of a specific interaction between two individuals.

The photo below shows what this may look like in practice. Here, my horse has primary access to a newly filled watertrough. He drinks first, while the rest of the group waits for him to finish. In this case, he is the “dominant” one. This doesn’t tell us anything about his personality or his innate qualities. It just tells us that in this particular situation, water was an important resource to him and he had dibs on it.

Sometimes things get confusing when ethologists speak of “dominant” versus “submissive” individuals2. While this may sound as if we are talking about discreet character traits, it should be understood as shorthand for “has primary access to a particular resource in a particular context” and not as a description of any personal quality or desire to dominate.

Dominance relationships are formed through interactions between two individuals over a specific resource. In many species - and certainly in horses - these interactions are highly context-specific. What I mean by this is that an individual that gets primary access to a resource in one situation may not do so in a different situation. Some things that can alter dominance relationships between two horses are:

changes in motivation (one horse is not hungry/thirsty at the moment)

the presence of a third individual (another horse or a human is around)

changes in the scarcity or abundance of a resource (the more limited a resource, the more pronounced the dominance relationship)

a different resource (a horse may have primary access to a bucket of feed, but not to another mares’ foal)

Contrary to popular belief, dominance interactions in stable groups are not primarily mediated through overt aggression. Often, the communication is much more subtle, and avoidance and appeasement seem to play a deciding part in negotiating and upholding dominance relationships. Aggression certainly factors into defending an important resource as and when necessary, but it is a much more nuanced spectrum of interactions than overt kicking and biting, and among well-socialised horses in stable social groups it is the exception rather than the norm. (If you are interested in learning more about aggression in horses, I have written about it in a series of previous posts, and done two presentations on the topic which are available online: in English for World Horse Welfare, and in Swedish for the Swedish association for reward-based horse training, BHIS.)

Importantly, dominance relationships are not the only relationships that matter to horses, and their social structure is not based solely on interactions over resources. Other relationships, such as familial or friendly relationships as well as cooperative alliances, are equally important in determining the various interactions in a group of horses. Friendships can even override dominance relationships, and two horses that are close friends will often share resources even when they are limited.

This is why speaking of dominance hierarchies or ranking in groups of horses is complicated. Generally speaking, the sum of all individual dominance relationships in a social group forms the basis of the group’s dominance hierarchy. But the word “hierarchy” implies a static system of authority, which is quite far from what we observe in horses allowed to live under naturalistic conditions. As we have seen, horses’ social interactions do not fit into a simple dominant-submissive dichtomy, and any attempt at constructing a useful social hierarchy will need to take other interactions, such as family ties and friendships, into account as well and not just interaction over resources.

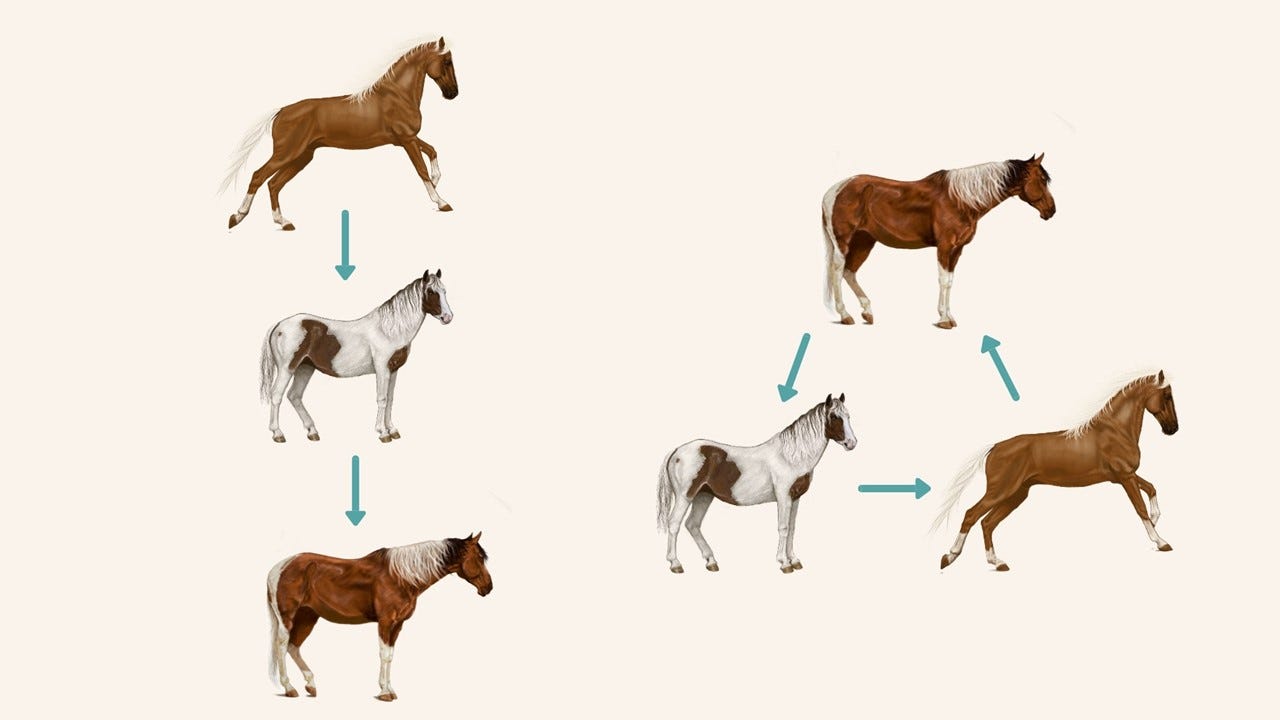

Even if we were to allow ourselves to focus only on interactions over resources, and reduce horses’ social lives into some kind of dominance hierarchy, that hierarchy would not necessarily be hierarchichal. There certainly are group structures that follow a broadly linear dominance hierarchy, meaning that horse A will have access to a resource before horse B, who will have access before horse C, and so on. But there are other structures, too, for example circular structures where horse A will have access before horse B, who will have access before horse C, who in turn will have access before horse A. The illustration below shows an example of what these two different structures might look like.

When we talk about “rank” or “rank relationships” in horses, we are referring to a linear dominance hierarchy where a horse “outranks” every horse below them. While such structures certainly do exist, I want to stress that viewing horses’ social lives merely through a lense of dominance is a highly simplified view that doesn’t take contextual interactions and other relationships into account, and that doesn’t even apply to many horse groups. Importantly, a horse’s position in a linear hierarchy will depend on the group composition. A horse that is high up in one linear hierarchy may well find themselves in the middle or bottom in another, or even in a non-linear structure. So while there seems to be some correlation between a horse’s age and the likelihood that they will end up higher in the “ranking order”, present rank is not a very reliable predictor of future rank. For these reasons, I would suggest that we retire “rank”, “rank relationship” and “dominance hierarchy” from the equestrian vocabulary, because they provide little to no useful information about anything.

Because the social structure of horses is so complex, any change to a group’s composition will disrupt established relationships in unpredictable ways. This often leads to a period of increased conflict as new relationships are worked out and a new structure is established. To an untrained observer this might look like “fighting for dominance”, but as we have seen, interactions over a resource is only a small part of the business two horses have with each other. Once a new social structure has been established - and provided we humans don’t meddle by confining them in small spaces and limiting their resources - there is generally very little further conflict.

Here’s an important qualifier to everything I have just said. We cannot enter our horses’ minds and understand the world like they do. Through ethological research we can edge ever closer to such an understanding, but it will always be an approximation because we are limited by our humanness. The world simply looks different to us, and our theory of mind can only get us so far beyond the species barrier. When we study social interactions in animals, we observe and describe behaviours from which we then try to infer meaning through comparative analogies from other species, including our own. But we can’t know for sure whether the meaning we ascribe to a behaviour or a series of behaviours corresponds with the animal’s actual experience. This is a fundamental principle of animal behaviour that we always need to keep in mind. Science provides us with data which we then use to construct ever more complex models of the world, but we need to remain humble to the fact that they are precisely that: models, not the real thing.

In the case of dominance relationships and dominance hierarchies, for example, we cannot say for sure whether they describe real, discreet social relationships, or whether they are merely a model through which we humans try to understand a subset of behaviours we see in a species in particular situations. What I mean by this is that we do not currently know if horses understand that they have a place in a social hierarchy and act accordingly, or if they simply navigate interpersonal relationships as and when necessary. For example, does horse A have some conceptual knowledge of their dominance relationship to all other horses in the group, and possibly even of the relationship between horse B and C? As our research into horses’ social lives progresses we might find out one day, but for now we have to submit to uncertainty.

To sum up, the idea that horses constantly fight each other for a place in a pecking order is simply not true. Dominance in horses is not a question of personal characteristics, but of the outcome of context-specific interactions over a limited resource which are not necessarily mediated through overt aggression. In stable social groups where resources aren’t limited, daily conflict levels are practically nonexistent. Additionally, horses social lives revolve around many other interactions than just who gets access to a particular resource, and friends can share resources. Horses social structures are quite complex, and even when reduced to “dominance hierarchies”, these are not always linear and a horse’s position in such a “hierarhy” will change between groups.

What does this say about the horse-human relationship? Well, as horses don’t constantly fight each other for the top spot, we have no reason to think they fight us. It simply does not seem to be a part of their social repertoire. Additionally, it is not clear whether the concept of dominance relationships applies to horse-human interactions, because we do not compete for the same resources.

Ok, now that we’ve discussed dominance at length, let’s turn to the even more nebulous concept of “leadership”.

What is “leadership”?

The idea of leadership is so fundamental to our understanding of horse-human interactions that one can hardly find any advice that doesn’t start with the need to “establish leadership” over the horse. This advice is applied regardless of whether the problem is a horse that won’t be caught, load into a trailer, or jump an obstacle. Any person outside the horse world with even the faintest critical thinking skills should immediately see that this makes no sense: how can such a diverse and multicausal range of problems all have the same solution?

Yet this is how many horse people view the world.

To understand why the horse world has gone down this intellectual cul-de-sac we need to first take a look at the lay definition of leadership. The Cambridge Dictionary defines a leader as someone “in control of a group, country, or situation”, and leadership as “the position or fact of being (in control of a group, country or situation)”.

The operative word here is control. As for dominance, control is an integral part of leadership, and in the context of horses, we mean specifically controlling movement. We say that “lead stallions” or “lead mares” move their groups away from danger or towards food and water, and that “being a good leader” to our horses means we can get them to walk past scary things. So we have a situation where dominance is defined as a desire to or an action to control someone else, while leadership is defined as the state of being in control of someone else. Thus, it becomes easy for us to assume a causal relationship between the two, that being dominant makes you a leader, and so the dominance-leadership complex is born.

This dominance-leadership complex creates a false narrative that there are certain dominant horses that have an innate desire to challenge our leadership. Viewed through this distorted lens, it becomes easy to assume that any time our horses refuse to do something we ask of them, they do so because they are rebelling against our leadership. They are, quite literally, being disobedient, i.e. “refusing to do what someone in authority tells (them) to do”. In this warped reality, horse-human interactions are reduced to a state of perpetual warfare where one must be the dominant leader and the other must be the submissive follower.

If we genuinely believe that the fundamental interaction between us and our horses is a battle for rank and that our horses are continuously trying to overthrow us, using force becomes not just a legitimate but a desirable action. But as we have already established, the first half of the dominance-leadership complex is a lie. Horses do not constantly fight each other or us for the top spot in an absolute hierarchy, and their social lives are much more nuanced and complex than just arguing over resources. Now let’s finish the job and debunk the second half, too, by taking a look at how horses actually confer leadership on each other.

“Leadership” in the ethological sense is generally defined as the initiation of movement in one or more conspecifics. Leadership is not defined by the actions of the leader but by the response of the followers, so when ethologists try to work out which individual in a group is a “leader”, we are mainly concerned with what all the other group members are doing. When assessing leadership in a group of horses, what matters is not which horse starts moving first, but rather which horses decide to follow.

There has been a fair bit of research into how horses structure their social lives, including how movement is initiated in various groups. While there is a lot left to discover, it seems pretty clear at this point that “leadership” is a shared activity. When horses are observed in naturalistic settings where they are allowed to make decisions without human intervention, there is no consistent pattern as to who moves first and who follows. Moving towards something or away from something seems to be a collective decision-making process, and while we still don’t know the details of how this is communicated, we can say with some degree of certainty that there seems to be no such thing as a “lead stallion” or “lead mare”. Pretty much any horse in a group can be followed by any other at any time.

As there seems to be a slight correlation with age, my best guess is that this has to do with competency. Horses will follow the one who is believed to have the right information and/or skills for a given task. A recent study by Valenchon et al. (2022) found a tentative indication that the perceived reliability of an individual may factor into it, in some sort of interaction with general popularity, but we still know very little about how all this plays out. Importantly, we see no connection between a horse’s place in the social structure and the likelihood that they will be followed by others. “Dominance”/“rank” are not reliable predictors of whether a horse will be a leader in any given situation.

This has serious implications for the dominance-leadership complex. Given that horses don’t seem to have specific leaders in their groups, there is no reason why they should ever consider one of us as their One True Leader. It seems to be an entirely foreign concept to them. Their natural inclination is towards shared, situational decision-making based on subtle communication that we have not yet been able to disentangle. Additionally, there is no connection between dominance and leadership. The foundational assumptions of the dominance-leadership complex have no basis in reality whatsoever. They are simply not true.

Now that the dominance-leadership complex is disintegrating before our very eyes, let’s deliver the coup de grâce: respect.

What is “respect”?

The Cambridge Dictionary defines respect as an “admiration felt or shown for someone or something that you believe has good ideas or qualities”. When we say that we want our horses to respect us, this is what we mean. We hope that they will evaluate our inner qualities and find them to be worthy of deference, so that deferring to us - i.e. submitting to our leadership - will be an active choice on their part.

The problem with this is that horses, to the best of our current scientific knowledge, do not have the ability to evaluate neither our ideas nor our qualities. We humans have evolved a cognitive capacity that is unique in the natural world. We need to accept that there are aspects of human cognition - such as abstract thought and the desire to share our abstract thoughts with each other - that other species do not have.

Cognitive capacity aside, horses and humans also don’t communicate in the same way. Our language-based form of transmitting ideas is well outside the realm of equine information transfer, and there is very little overlap in our species’ communication strategies. Horses and humans simply do not have the shared tools to evaluate each others’ thoughts. And it follows that if horses can’t evaluate our ideas, they can’t admire and respect them, either.

There is no ethological definition of respect. It is not a concept that is studied in animals, because there is no way to operationalise it the way we can operationalise “dominance” or “leadership”. What would it look like when a horse feels an admiration towards someone they believe has a good idea? What behaviours would we see? What data would we be gathering?

When I say that your horse doesn’t respect you, I don’t mean that they disrespect you. I just mean that they lack the ability to respect or disrespect. They certainly have an opinion about you, but it is based on how you have treated them in the past rather than on any admiration of your inner qualities.

But admiration is not the whole story when it comes to respect. There is also an undercurrent of fear. When we show respect, we do so because we fear the consequences of not showing respect. We respect our managers because we don’t want to get fired, we respect the authority of the law because we don’t want to go to prison, and so on. In our society, the act of disrespect comes with a price tag, even if that price tag is just incurring the judgement of others. There is also a clear connection to dominance and leadership here. We are expected to show respect to those who are superior to us in the social hierarchy, whether that is our line manager or a police officer, or an idea that governs our society, such as a legal code.

And this is also what we expect from our horses. We want them to respect us as their leader, i.e. as the dominant one in our social hierarchy of two. And just as in society, the way we go about achieving this in practice is by making them fear the consequences of not respecting our authority. The sad truth is that most of the behaviours we euphemistically label as “respectful” are fear-based, because they have been achieved by punishing alternative behaviours. Take a horse that has learned to stand still because he has been forced to run in small circles every time he has tried to move, for example. That horse does not stand still out of any admiration for his trainer’s inner qualities, but because being chased around in small circles is scary and unpleasant, and he would rather not have to experience that again.

A horse trained within the dominance-leadership complex does as he is told because if he doesn’t, he gets punished, whether that’s a raised voice or a smack with the hand or “hustling his feet” or some other correction. A horse trained in this way is not well-behaved because he is respectful, but because he is afraid of you. And this is the terrible and inevitable consequence of the dominance-leadership complex: a relationship based on fear. And not just fear by accident, but by design.

At this point I feel quite confident in asserting that the vast majority of us don’t want our horses to be afraid of us. So now that we have buried the dominance-leadership in that proverbial unmarked grave, how can we move on to build an evidence-based and compassionate relationship with our horses?

The way forward

A key thing to understand about “the horse-human relationship” is that it is not one relationship. It is not a monolithic concept. Every horse and every human will have unique relationships based on their personalities, affinities, current interactions, and past history. My horses, for example, have a different relationship with me than they have with my partner, or with their farrier, or with the cyclist we meet on our walks. This relational diversity is often forgotten, but important to keep in mind.

We are still discovering the cognitive and emotional building blocks that make up horse-human relationships, but a general rule of thumb is that a relationship is the sum of all previous interactions. This means that if you and your horse have mostly positive interactions with each other, your relationship will be a good one. While this is a useful model when thinking about how to build a good relationship with our horses in practice, in can become a bit transactional, and real life is often messy. At any one time, an individual - whether horse or human - will be experiencing multiple and often conflicting emotions and motivations, which may affect their perception of their relationships. Just think about how you love spending time with your horse but also constantly worry about his health and dread having to pay vet bills. One relationship, several different (and often simultaneous) emotional experiences.

What role should ethology play in understanding horse-human relationships? Quite a prominent one, in my opinion. It is fair to assume that neither we nor horses can form relationships in ways that are alien to our biological capabilities. A horse-human relationship forms at the intersection of the lifeworlds of two very different species, and each species will only be able to perceive the other within the constraints of its sensory, cognitive, emotional, and social capacity. To take a familiar example, horses can’t respect us because evaluating our ideas lies outside their cognitive remit.

There is still a lot for us to discover when it comes to horses’ social capacities, both towards each other and towards other species. I am convinced that the relationships they form with us are likely to be as complex as the ones they form with each other. This doesn’t mean, however, that they are exactly as we would like them to be. We have no reason to think that our horses miss us when we’re not around, or see us as partners in competitions or as comrades on a battlefield. No, horses are horses, and they form relationships that make sense to them.

So what might that look like?

We need to start with what we know about their social lives. They do not live in absolutist hierarchies. They form strong bonds that last for life. Mutuality and reciprocity are important elements in their decision-making. Their communication is subtle and nuanced. Friendships are more important than dominance relationships. These are things that we need to keep in mind when trying to work out how to interact with them across the species barrier. At the very least, we should not attempt to implement practices that are alien to them, such as dominance-based social orders.

We also need to make sure we sidestep the trap of thinking we can somehow become a part of our horse’s social group. This is a mistaken belief that we find both within the dominance-leadership complex and among those who shun it, but we can’t fool a horse into thinking we are a horse. They know that we are not horses but something other than horses, so simply trying to mimic how they interact with each other in order to slot into their social structure is not going to work. For one, we lack the fundamental tools to communicate with them in their own language, such as mobile ears and tails. We also don’t spend our days and nights living with them, and our behavioural biology - such as our sleeping and eating patterns - are very different. Horse-human relationships are fundamentally cross-species interactions, where two individuals of different species learn each other’s idiosyncracies and adapt to a shared environment. To me, this is an amazing thing. We don’t need to embellish horse-human relationships with pseudoscience and airy-fairy BS to appreciate how incredible it is that two different species can learn to enjoy each other’s company.

With all that said, I know you haven’t read this far just to leave without some kind of concrete advice. Below, I have listed four things you can think about when interacting with your horse, in order to build a good relationship. Perhaps I will expand on them in another post, but for now, here’s my advice:

Think about your horse’s experience. Don’t focus so much on what you are doing in any given situation, but instead, think about how your horse might be perceiving that situation. This goes well beyond choice of training method and equipment, although these matter too, of course. Consider whether your horse might be hungry? Thirsty? Unsafe? Too warm? In pain? Alone? Frustrated? Coerced? Strive to be the person that makes good things happen to your horse, and that makes bad things better, regardless of your own plans and ambitions.

Be reliable. Your horse should be able to trust you to be the bringer of good things and the fixer of problems. This means that you need to be predictable in your actions and demands. If your horse can never quite know if being around you will be pleasant or unpleasant, if you will fix a problem or create one, you will build a lot of emotional ambiguity into your relationship.

Stay below threshold. Stress, pain and fear are not all-or-nothing. All the little stressors add up over the course of a day, a week, or even a lifetime, until they reach a critical point where the horse can no longer cope with the negative emotional buildup and reacts strongly with either flight or aggression. This critical point will be different for every horse, but if you always strive to be the person that takes away stress and pain, whether physical or emotional (see point 1 above), that will go a long way towards having a safe and pleasant relationship.

Respect your horse for who they are. But, I hear you say, wasn’t respect a non-starter in the horse-human relationship? Yes. For the horse. But not for you. While you should never demand respect from your horse, I firmly believe that you need to respect them. The Cambridge Dictionary has another definition for the word respect: “a feeling that something is right or important and you should not attempt to change it or harm it”. I think this definition goes to the core of our responsibilities as horse owners and carers. When we choose to engage with our horses, we should do so because we like them for who they are, because they are right and important as themselves. We should acknowledge not just their species-specific needs - their “horseness” - but also their individual needs, and make allowances for their existence in our strange human world. So while horses can’t respect us, we certainly can - and should - respect them.

All opinions expressed here are my own.

This post is free for anyone to read. It takes time and effort for me to write these posts, so if you liked it or found it interesting, please consider commenting, sharing it with a friend, or sharing it on social media as a thank you! And if you want to get notified when I post next, please consider subscribing. That’s also free!

Pseudoscience is definied by the Cambridge Dictionary as “a system of thought or a theory that is not formed in a scientific way”. The insidious thing about pseudscience is that, like a wolf in sheep’s clothing, it superficially mimics elements of true science to deceive people.

When it comes to horses, I am not convinced that there are any clear submissive behaviours because the types of behaviours horses display during and after a dominance interaction can be displayed by both parties, regardless of the outcome.

This is such a great, in-depth post, that every single horse person should read!

I have a small farm, Al Sorat Farm, in Giza, Egypt, with a few horses most of whom have been with me for over 20 years. My academic background was social psychology about fifty years ago because there was no label for looking at animals and humans in an ethological framework. I started my farm when my kids had gone off to NYC for their university experiences and my husband had died in an accident. During the past 20 years, my horses, my dogs (a pack of 14 that stays at that number because the dogs chose it), and I have been studying the behaviour of social animals at the farm, while being engaged in therapeutic activities, school classes, and other things. I find it fascinating that the veterinary schools in Egypt have no space for teaching animal behaviour to the vet students, although to study it before anything else seems a total no-brainer to me. So I am now looking at how to offer this study here at my farm. Your article is brilliant and lit up my heart and my head. I will be following closely. I will be recommending The Equine Ethologist to all my friends.