This video, which is a few years old now, shows my gelding (the buckskin) displaying clear stallion-like behaviour towards another gelding (the palomino).

The context is the following (because context is everything when interpreting behaviour): the palomino is a client horse that has just arrived. My two horses, who have lived alone in a stable social group for over a year at this stage, are in their usual field, while the new horse is in a smaller, adjacent field. They can see each other, but not touch each other. All three are well-socialised geldings.

So, what is going on here?

Horses, unlike other equids such as donkeys, are generally not territorial. Instead of protecting a location, they protect the integrity of their social group by differentiating between horses who are part of it and those who are not. One way horses negotiate and maintain within-group relationships is through proximity (not unlike us: think about who we let into our homes and personal spaces - it is generally people we know well and like).

When unfamiliar horses come too close to an established social group, horses in that group will often display agonistic1 behaviours towards the stranger to keep them at a comfortable distance. While both male and female horses will take responsibility for protecting the integrity of the group, this role is particularly pronounced for stallions.

Horses have evolved to live on large home ranges which they share with many social groups. In order to avoid constant fighting over group cohesion, horses have evolved comlex ways of communicating with each other, such as subtle facial expressions and body language (see for example the Equine Ladder of Aggression), and a generally polite attitude where they respect each others boundaries.

The ritual of stallion aggression

One particular subset of agonistic behaviours is inter-male aggression. For horses, the behaviour patterns associated with inter-male aggression have become highly ritualised over time, to the point where some have become fixed, repetitive sequences.

The point of such ritualised displays is for two (or more) stallions to make visual and olfactory appraisals of each other and work out who would ‘win’ a potential fight, without the fight actually having to happen. This is a great survival strategy, because it can lead to effective conflict resolution without injuries.

So what do these ritualised displays look like?

In 1995, McDonnell and Haviland published the Agonistic ethogram of the equid bachelor band2, which lists 49 elemental agonistic behaviours that can be observed in male-male conflicts. The ethogram also features three complex behavioural sequences, made up of individual behaviours from the ethogram:

Fecal pile display, a specific olfactory-behavioural interaction where the stallions inspect and defecate on each others piles

Posturing, parallell movement and sniffing each other involving arched necks, high steps, general tension in the body and ‘passage-like’ movement

Ritualised interactive sequence, a consistently ordered behavioural sequence that combines the two aforementioned sequences

If we look at the video, we can identify a number of behaviours from the agonistic ethogram that my horse (the buckskin) is directing at the newcomer (the palomino):

Sniffing feces

Strike with front leg

Stomp with hind leg

Approach/parallell prance

Head bowing

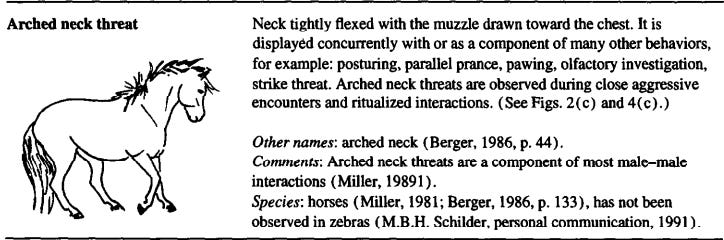

Arched neck

Pawing

This sequence is then repeated a few times, in roughly the same order, interspersed with calming/appeasement behaviours such as turning the back and sniffing the ground.

Why are calming/appeasement behaviours part of a ritualised aggressive display?

Because the purpose of ritualised stallion aggression is to avoid a conflict. The buckskin is communicating to the palomino that while he is prepared to fight to keep his social group safe, he would prefer not to.

And because equine communication is a conversation, not a monologue, and because horses are experts at polite conflict resolution, the palomino replies to this display by mirroring the calming/appeasement behaviours and eventually turning away, signaling that he is not a threat.

Once he does, my horse feels that he can disengage and come to me. (Notice also that he is licking and chewing as he does so, indicating that the encounter was stressful.)

Why some geldings act like stallions

Ok, so far so good, but the question in the title remains - why would a gelding behave like a stallion?

The short answer is: because he doesn’t know he is a ‘gelding’. Castration is not a naturally occurring state3 in horses, and so there is no biological blueprint for how a ‘gelding’ should behave. Biologically, they are just ‘males’, and behave accordingly - which includes taking on the role of protecting the social integrity of their group.

But doesn’t castration lower testosterone levels?

Yes, but hormonal profile is just one factor that influences behaviour. Castration can raise the individual threshold for inter-male aggression and lower the sex drive, but it does not remove the neurological pathways, cognitive appraisal, emotional capacity, or behavioural motivations for aggression.

Remember, aggression has evolved to serve important purposes and is thus a deeply conserved complex of behaviours with many causes and triggers. Snipping off a pair of testicles will not undo 50+ million years of behavioural evolution (and longer still, as we find aggressive behaviours not just in mammals but across the animal kingdom).

Importantly, aggression is a social behaviour. Foals and youngsters learn to regulate their emotions and fine-tune their communication by observing and interacting with older horses. While social and individual identity in horses is not well-researched, there is evidence that male and female horses learn different behavioural patterns. Colts will play and interact with mature stallions in their social group, and through this process pick up their behaviours.

My horse, for example, grew up with his father and spent two years learning ‘gendered’ social communication from him. Despite being castrated young and never showing any sexual interest in mares, these ‘stallion-like’ behaviours and behavioural patterns are still relevant to him, because they are not related to hormonal profiles or sexual drive, but to his role as a male horse in a stable social group.

I keep coming back to this, but it really cannot be over-stated: behaviour is complex and contextual. We need to be very careful not to essentialise it into neat one-factor models such as ‘arousal’ or ‘hormones’ or ‘dominance’ or ‘pain’, because they do not reflect the reality. There will always be multi-factorial interactions and individual variability, and it can be tricky to disentangle the various causes when analysing a sequence of behaviours.

In the case of stallion vs. gelding behaviours, we also need to remember that ‘gelding’ is a human construct, physically as well as conceptually, and our expectations of how a gelding should behave do not always match the reality of being a male horse.

But this is the beauty of studying animal behaviour - if we are humble enough to put down our anthropocentric blinders, we can, however briefly, glimpse a different reality and see the more-than-human world around us.

All opinions expressed here are my own.

This post is free for anyone to read. It takes time and effort for me to write these posts, so if you liked it or found it interesting, please consider commenting, sharing it with a friend, or sharing it on social media as a thank you! And if you want to get notified when I post next, please consider subscribing. That’s also free!

Agonistic behaviours involve both aggressive and avoidance behaviours.

McDonnel S M, Haviland J C S. 1995. Agonistic ethogram of the equid bachelor band. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 43(3), p. 147-188.

The interaction between sex and gender is well researched in our own species, but as with everything else, it must have an evolutionary background. As far as I am aware, we don’t know exaclty when ‘gender’ as an individual identity evolved in primates, or what the earlier stages might have been, but it is intriguing to think about whether other animals have an understanding of their social roles and how it relates to their biological sex.

Share this post