I find myself increasingly disillusioned by the riding school model. Barring a few theory sessions every term, in most cases there is little actual knowledge being disseminated. Riding schools might teach you how to ride, but they don’t teach you much about horses.

Modern european riding schools are the remnants of a militarised educational system (in my native Sweden, for example, they quite literally became a repository for decomissioned cavalry horses after WWII), developed to teach recruits how to not fall off. Horses and riders were tools to be used in the great theatres of war.

This militaristic culture has largely remained in place, even though we no longer aim to send children and their ponies into battle: training follows a rigid, linear progression focused on specific maneuvers, riders obey instructions to ‘turn down the centre line’ in unison, and there is little room for individualised lesson plans.

It is a thoroughly outdated system that does not align with the increased focus on the horse-human partnership and relationship-building as pillars of equitation.

Importantly, most riding schools don’t teach their riders how to understand the exceptionally complex being they are sitting on. Horses’ sensory perception, social cognition, emotions, and learning are rarely explored in any depth - largely because the horse world in general is terrible at engaging with science.

This isn’t fair to the horses.

It is a hard life, being a lesson pony. They work for several hours a day, 5-6 days per week, carrying around a variety of unbalanced riders in the same repetitive patterns year after year, wearing down their bodies (one study found that 74% (!) of riding school horses were affected with back problems that could be traced to rider posture1). Many are kept in individual stables with little turnout, in noisy and busy facilities, forced to endure handling by a constant stream of unfamiliar children and adults and tacked up by inexperienced hands.

It is both physically and emotionally taxing, yet the welfare of horses and ponies in riding schools is not really talked about in relation to Social Licence-issues. I think this is due to two things: firstly, we tend to see riding schools as fundamentally 'nice’ establishments, as they are run for no or low profit and often cater to children (compared to, for example, racing and sport). This is demonstrated well by EU law, which considers riding school horses to be ‘leisure’ horses rather than ‘sport’ or ‘working’ horses.

Secondly, the specific conditions of riding school horses and ponies have been poorly researched, although this is slowly changing. Hot off the press is the study Work it out: Investigating the effect of workload on discomfort and stress physiology of riding school horses (2023) by Ijichi et al2.

The researchers set out to assess how lesson horses are affected by their work load. They tested 30 horses (19 geldings and 11 mares) from one riding school under three conditions: on a rest day (0 hours of work), on a moderate work day (1-2 hours of work), and on a hard work day (3-4 hours of work).

On each of the work days, the horses were brought into their stables after the lessons and allowed to settle down for one hour, then the researchers measured:

Eye temperature using a thermal imaging camera

Heart rate variability using a heart rate monitor

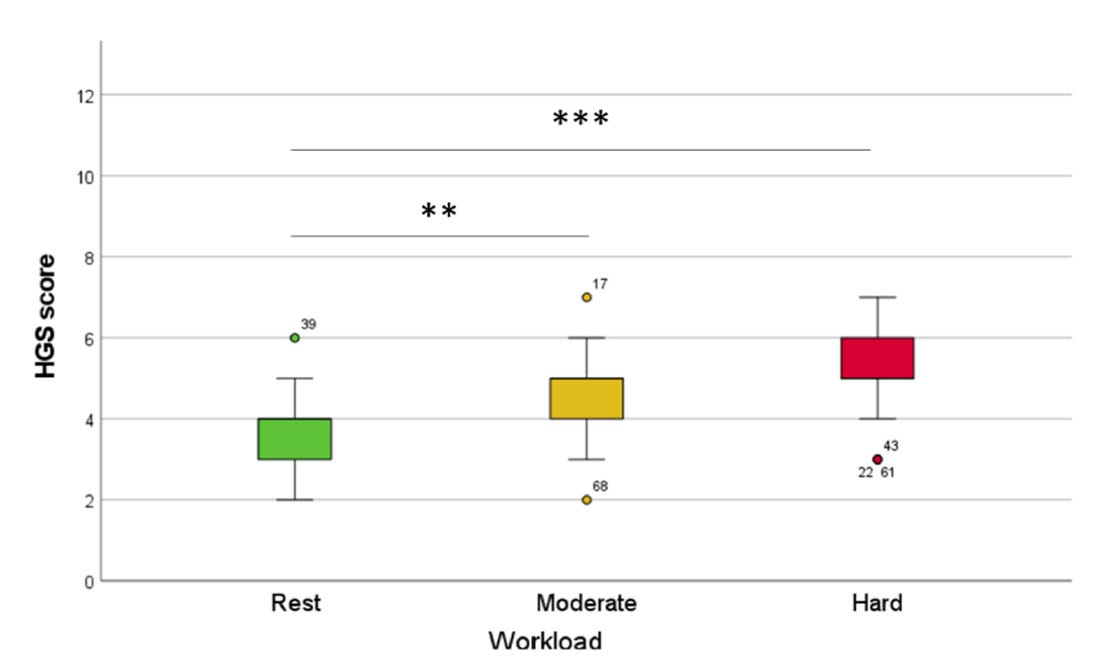

Facial expressions indicative of discomfort, assessed with the Horse Grimace Scale (HGS; this is similar to the Equine Pain Face, but developed independently by Dalla Costa in 2014 to assess post-surgical pain in castrated horses3)

The researchers found that eye temperature and heart rate variability did not differ significantly between the work loads, likely because these measures are affected by physical exertion and the one-hour resting period may have simply allowed them to return to baseline.

They did, however, find a significant increase in discomfort-related facial expressions (ears pointing stiffly backwards, tightening of the eye area, tension above the eye area, tension around the jaw muscles, tension around the muzzle, tension around the nostrils) as work load increased.

This means that lesson horses displayed significantly more signs of discomfort the longer they worked in one day.

Below are three photos to visualise the facial expressions in the different work conditions. What stands out to me - and the authors note this in the discussion as well - is the fact that the horses had fairly high HGS scores on their rest days, too. I find this really quite remarkable: these riding school horses seem to live in a state of chronic discomfort!

As distressing as this realisation may be, in fairness, it does not surprise me. A few years ago I worked briefly as manager of a riding school (it was a brief stint because I could not bear it for more than a few months), and all the ponies displayed an array of pain- and discomfort-related behaviours, ranging from extremely high levels of aggression towards people to reactivity under saddle or not wanting to move at all.

This is, of course, not something anyone wants. But it is a reality we need to face. While there is huge variability between riding schools in terms of work load, management (single or group housing), feeding strategies, and welfare of the lesson ponies, it is clear that there is a broader conversation here that needs to be had.

Fundamentally, I believe we need to rethink the entire riding school model, because the current approach is outdated and clearly puts horses and ponies at risk of physical and emotional suffering. But I think a better way is possible.

What might a modern, evidence-based riding school look like?

Below are some of my suggestions, as an equine ethologist and former riding instructor.

I acknowledge that some of these points may seem quite radical and require a thorough re-thinking of both operations and budget. However, I don’t think it is necessary to go all-in - even small adjustments can make a huge difference!

Species-appropriate housing and management for all horses and ponies. This means group living in enriched paddocks, 24/7 foraging opportunities, access to soft and dry communal sleeping areas, and minimal time indoors.

Greater focus on the needs and experiences of the horses in management and lesson plans, including a ‘horse says no’-protocol if a horse clearly communicates that they do not want to participate in an activity.

Less focus on riding, particularly at the lower levels, and more focus on learning how to properly understand horses as living beings: their social communication, their behavioural needs, how they learn. This should be integrated into the lesson plan at every stage.

Longer lessons that incorporate supervised preparation and tacking up. This would both facilitate learning about non-ridden horse handling and care, allow students to have more positive interactions with their lesson horses outside of riding, and decrease the risk of stressful and inexperienced handling.

A strict 3-hour daily work cap4 and sufficient redundancy in the number of horses so that illness or injury doesn’t lead to the other horses having to work more hours.

Individual exercise and health plans for every horse, as well as two days off every week, one week-long holiday in the middle of every term and minimum four weeks off every summer to allow for physical recovery.

More varied lessons that incorporate regular non-ridden work, including relationship-building activities such as exploration walks, grazing in hand, or positive reinforcement-based trick training.

An integrated relationship between theory and practice in lesson plans, so that progression is based on understanding of equine ethology and learning theory as well as riding skills. The first thing every novice should learn, for example, is appropriate reinforcement techniques (both positive and negative reinforcement) and how to think creatively about problem solving without simply resorting to escalating pressures.

Clear, science-informed language from instructors (less ‘he’s just being cheeky, ride it out’ and more ‘he is telling us that he is struggling to cope with the situation right now - what might we do to help bring his stress levels down?’).

Increased use of positive reinforcement, environmental affordances and other motivational techniques rather than simply escalating pressure, and a complete ban on spurs, whips, leverage bits and side reins.

I acknowledge that this is a fundamental shift away from the current riding school model, but that is the point. And, importantly, the shift is already happening!

There are riding schools all over the world who are successfully re-imagining what learning about horses can be like. Some examples include SK Equestrian Academy in Montana and Stall Lyckoklövern in Sweden, which offer horsemanship lessons based on positive reinforcement, or Lindingö Ponnyridskola in Sweden which offers traditional lessons but keeps all ponies in outdoor group housing 24/7, or Malath Paddock Paradise in UAE which keeps all horses on a track system, use bitless bridles, and incorporate lessons in horse behaviour and care alongside riding.

I hope the rest of the horse world will take its cue from these innovators who have embraced science as an opportunity to create new and better practices.

Finally, I want to give a shout-out to the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences research project Hästvälfärd på ridskolor, which aims to improve the understanding of equine behaviour and learning at Swedish riding schools.

All opinions expressed here are my own.

This post is free for anyone to read. It takes time and effort for me to write these posts, so if you liked it or found it interesting, please consider commenting, sharing it with a friend, or sharing it on social media as a thank you! And if you want to get notified when I post next, please consider subscribing. That’s also free!

Lesimple C, Fureix C, Menguy H, Hausberger M (2010) Human Direct Actions May Alter Animal Welfare, a Study on Horses (Equus caballus). PLOS ONE 5(5): 101371.

Ijichi C, Wilkinson A, Riva M, Sobrero L, Dalla Costa E (2023) Work it out: Investigating the effect of workload on discomfort and stress physiology of riding school horses. Applied Animal Behaviour Science 267: 106054.

Dalla Costa E, Minero M, Lebelt D, Stucke D, Canali E, Leach MC (2014) Development of the Horse Grimace Scale (HGS) as a Pain Assessment Tool in Horses Undergoing Routine Castration. PLoS ONE 9(3): e92281.

Provided the work is low-intensity, varied, and not stressful.

In fact most non-equesterian people search for riding (for themselves, for their children). Only a few come to stables because they want see and feel horses, most want to look beautifully on a horse and the stream of clients is fast. I find this is a problem that has been cultivated by cultural features (horses = riding goes through our history) and by riding schools themselves, that offer nothing but riding.

Another wonderful thought provoking post