A bitless bridle is only as harsh as the rider's hands

New evidence suggests bitless alternatives can cause tissue-damaging pressures

This post is free for anyone to read. It takes time and effort for me to write these posts, so if you liked it or found it interesting, please consider commenting, sharing it with a friend, or sharing it on social media as a thank you! Also, if you want to get notified when I post next, please consider subscribing. That’s also free!

All views expressed here are my own.

Bits and nosebands have a central place in the current welfare debates in horse sport. Last winter, the FEI ruled that double bridles should remain mandatory at GP level dressage, going against the recommendations of their own Equine Ethics and Wellbeing Commission and expert opinion. Recently, a Swedish petition to ban tight nosebands reached almost 18 000 signatures in a matter of days after images from the annual Falsterbo Horse Show caused outrage.

The social media outcry in turn prompted a respected Swedish veterinarian to publicly claim that in his 39 years as an equine vet, he had never seen any tissue damage from tight nosebands. Given the overwhelming scientific evidence and industry-wide consensus that bit- and noseband-related lesions are common in ridden horses, he can’t have been looking very closely.

But the whole thing does beg the classic question: is the bit really the problem, or is it the rider’s hands?

Studies that have compared horses’ behaviour in bitted and bitless bridles are inconclusive. While some have found a decrease in discomfort-related behaviours in bitless bridles, others have not.

High noseband pressures in bitless bridles

A recent study by Robinson and Bye (2021), Noseband and poll pressures underneath bitted and bitless bridles and the effects on equine locomotion1, took a different approach. The authors measured noseband pressures during ridden exercise in three different bridles:

a standard snaffle with a cavesson noseband where the reins attach to the bit

a bitless side-pull where the reins attach to either side of the noseband

a bitless cross-under where the reins attach to leather straps that cross underneath the horse’s jaw

A small sample size of five horses was used for the study. Each horse was tested under standardized conditions over three consecutive days, wearing a different bridle each day so that all horses were tested in all three bridles. During the tests, the bridles were fitted with pressure gauges under the noseband.

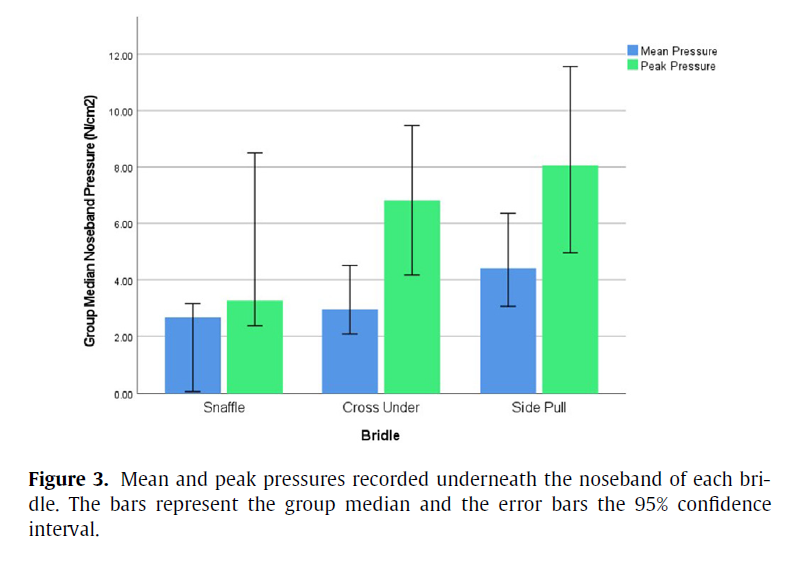

The recorded mean and peak noseband pressures were higher for the two bitless bridles than for the snaffle, although only the difference between the side-pull and the snaffle was statistically significant. In other words, the horses experienced the highest noseband pressures in the side-pull and the lowest noseband pressures in the snaffle.

This is not entirely surprising, since the side-pull is the only bridle of the three where the rider exerts direct pressure on the noseband. As the authors state: “with the absence of a bit, any rein tension must be directed to other facial tissues.”

Importantly, the average noseband pressures in all three bridles were high enough to restrict blood flow to the tissues in an exercising horse if maintained over a longer period of time. The side-pull was of particular concern: based on the authors’ calculations, an exercising horse would need over 205 mm Hg of pressure to restrict blood flow, with the side-pull pressure averaging 332 mm Hg (compared to 200 mm Hg for the snaffle and 221 mm Hg for the cross-under).

It is worth noting that the snaffle noseband was fitted according to the FEI ‘two fingers between noseband and face’ guidelines, meaning it was not nearly as tight as is common practice. It is therefore likely that the actual pressures horses experience from the noseband are much higher - in fact, Casey et al. (2013) found that pressures from crank nosebands could range from 200 to 400 (!) mm Hg, “pressures that, in humans, are associated with nerve damage and other complications”2.

Robinson and Bye (2021) also found that the horses had a significantly greater head-neck angle in the cross-under bridle compared to the snaffle. This is likely an effect of the bridle mechanics: the design of the cross-under means that pressure is applied under the horse’s chin, making the horse lift its head to avoid it, whereas the snaffle exerts pressure on the horses jaw, making the horse bend its head to avoid it.

Less pressure, not just different pressure

Despite the small sample size, the study nicely demonstrates two important things to consider when selecting and using equipment:

All tack will by design have certain mechanical effects on the horse, regardless of the amount of physical pressure we apply.

Any physical pressure we apply will always need to go somewhere, and that somewhere is the body (skin, nerves, blood vessels, bone) of our horses.

While bits increase the risk of discomfort and harm (this has been extensively researched and discussed elsewhere; I have written about it here, for example), simply applying the same pressure through a noseband is not the solution. Rather, we need to start riding with less pressure.

One of my biggest pet peeves is the concept of maintaining an ‘even contact’ on the reins. It is ubiquitous in modern riding, and yet it makes no sense from either a practical, training, or welfare perspective.

From a practical perspective, it is unattainable. Rein tension studies repeatedly demonstrate large variations in the pressure on the horse’s mouth, even with the same rider. There simply is no such thing as an ‘even contact’.

From a training perspective, maintaining constant (but inconsistent, see above) pressure on the mouth simply habituates the horse to it, making the horse less sensitive to subtle rein aids and less responsive to stop cues.

From a welfare perspective, combining pressure on the mouth with forward-driving aids in effect means asking the horse to move both faster and slower at the same time. Such a request is naturally impossible for the horse to comply with, which risks leading to behavioural conflict, frustration, and potentially a state of shutdown.

Is it the bit or the hands?

Going back to the question at the beginning of this post: is the bit the problem, or is it the rider’s hands?

Both, I would say.

Bits are definitely a problem, because, anatomically speaking, there is no room in the horse’s mouth for one. Young or inexperienced horses will respond negatively to the introduction of a bit3, suggesting bits are naturally perceived as something unpleasant. Given the growing body of evidence for the many physical and behavioural problems associated with bit use, and the evidence that they aren’t necessary for either control or performance4, there is good reason to do without them.

But as Robinson and Bye (2021) so nicely demonstrate, simply swapping one piece of equipment for another and using it the same way is not good enough. Pressure needs to go somewhere, regardless of what the reins are attached to.

Instead, we need to start re-thinking the very fundamentals of how we use equipment to communicate with our horses, particularly the outdated and unscientific concept of ‘even contact’.

Nuno Oliveira, a great master of classical dressage, said it better than I ever will:

“It is only by allowing horses to move on a free rein, and not in holding them in, that success may be obtained. Riders who hold in their horses are insignificant riders and will never advance.”

This applies to bitted and bitless bridles equally. Choosing bitless tack does not absolve us from using it with kindness.

Robinson, N., Bye, T.L. 2021. Noseband and poll pressures underneath bitted and bitless bridles and the effects on equine locomotion. Journal of Veterinary Behavior 44, p. 18–24.

Casey, V., McGreevy, P.D., O’Muiris, E., Doherty, O. 2013. A preliminary report on estimating the pressures exerted by a crank noseband in the horse. Journal of Veterinary Behavior (8), p. 479-484.

Quick, J.S., Warren-Smith, A.K. 2009. Preliminary investigations of horses' (Equus caballus) responses to different bridles during foundation training. Journal of Veterinary Behavior 4(4), p. 169-176.

Luke, K.L., McAdie, T., Warren-Smith, A.K., Smith, B.P. 2023. Bit use and its relevance for rider safety, rider satisfaction and horse welfare in equestrian sport. Applied Animal Behaviour Science (259), 105855.

Could you do research and write and article about humane and effective ways to communicate with our horses with reins attached? I know it starts and ends with the feel and timing.

Do we really need any tight nose band that restricts the opening of the mouth? Can we be kind and still be effective with a bit? I do my best to try and stay out of my horses way and try to let him explore and figure out the communication with my aids.

"It is worth noting that the snaffle noseband was fitted according to the FEI ‘two fingers between noseband and face’ guidelines, meaning it was not nearly as tight as is common practice." There's the rub. I attend more than a few CSI's and CDI's and I am always disturbed by how tight I see riders pulling the nose bands. But, I am even more disturbed by the abuse of the bit.