This post is free for anyone to read. It takes time and effort for me to write these posts, so if you liked it or found it interesting, please consider commenting, sharing it with a friend, or sharing it on social media as a thank you! Also, if you want to get notified when I post next, please consider subscribing. That’s also free!

Last month I gave a lecture in which I briefly outlined the biological underpinnings of animal emotions and discussed whether horses are capable of loving their owners. It was quite popular, so I decided to adapt it for a Substack post for Valentine’s day.

So, can horses love their owners?

What is love?

In order to answer the question, we first need to define “love” from an ethological perspective. When studying animal emotions, we can’t ask them outright how they feel. We can only observe their behaviour, because every behaviour has an underlying emotion. This is an evolutionary advantage: if you feel very strongly about something, it will motivate you to act, for example seek out an important food source or run away from a predator.

At the most basic level, emotions can be categorized as either good or bad. Just like humans, horses will approach something that makes them feel good, and avoid something that makes them feel bad. By observing how horses behave in certain situations, we can infer how they feel about them.

Emotions are not all-or-nothing. The intensity can vary: for example between strong aversion, leading to full out flight, and mild aversion, which will only manifest as stepping away.

This can be illustrated as a scale, like this:

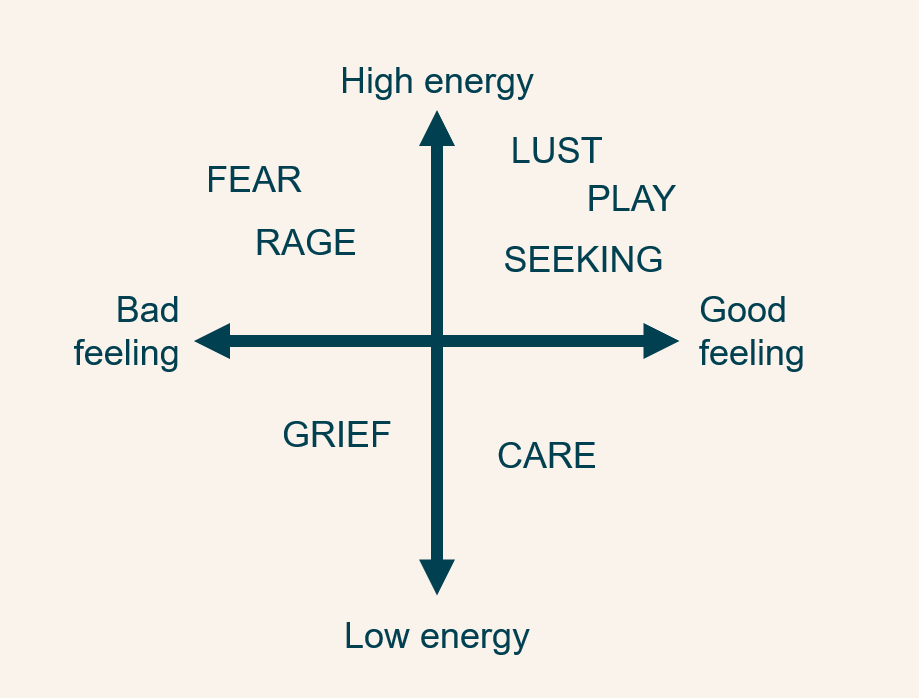

But there’s another dimension to emotions, too. You can feel good or bad about something in a high-energy state or a low-energy state. Think about these situations: you’re having sex (happy, high energy) or lounging on the couch watching your favourite show (happy, low energy). You’re running from an attacker (terrified, high energy) or sitting in an airplane seat anxious about crashing (terrified, low energy).

This is best illustrated as a y-axis that intersects the good/bad x-axis, like this:

This model is useful when assessing horse emotions. By observing basic behaviours such as approach/avoidance, aggression/friendliness, and energy levels we can map out what a horse’s current emotional state is and how it changes over time.

Another model we can use to understand horse emotions is Panksepp’s theory of core emotions, which I quite like and find really applicable. Jaak Panksepp was a neurobiologist who pioneered the research field of affective neuroscience, i.e. the study of the neurological basis of emotions. By comparing behaviours in humans and other animals, and observing which neural pathways were activated, he concluded that there are seven core emotional circuits in the brain that are evolutionarily conserved in all mammals. He divided them into positive and negative emotions.

Positive emotional circuits (my very general functional definitions in brackets):

SEEKING (expecting a positive outcome)

PLAY (having positive social interactions)

CARE (caring for something or someone)

LUST (sexual arousal)

Negative emotional circuits (my functional definitions in brackets):

FEAR (being afraid for your life)

GRIEF (being afraid to be alone)

RAGE (anger, aggression)

As you can see, these are different from the terms we normally use to describe how we feel, but I find them quite useful in terms of describing the behaviours our horses display and the underlying emotions that drive them.

If we think about the energy levels for each of the seven core emotions, we can plot them into the graph above, which could look something like this:

Now, where would ‘love’ fit on this graph? We can probably agree that it’s a good feeling, so it would be situated on the right side of the x-axis. In terms of energy level, I would say ‘love’ is a rather relaxed state, which would place it in the lower right quadrant.

From this we can tentatively deduce that ‘love’ is a nice, calm feeling, corresponding to Panksepp’s core emotion of CARE.

Can horses love?

The next question we have to answer is whether horses have the capacity for this kind of ‘love’. Here we have to look at the behavioural biology of horses as a species. Would ‘love’ be an evolutionary advantage for them?

Horses are group-living, social animals. Belonging to a stable social group with low levels of conflict is an important survival strategy. In order to maintain this stability, they differentiate between group members and non-group members, and protect the integrity of the social group from outsiders.

They also form complex relationships within the group and show clear preference for certain individuals over others. These friendships are mediated through affiliative interactions such as physical proximity and mutual grooming. From studies and observations we know that horses recognise each other and can maintain strong bonds over long periods of time, sometimes even a lifetime.

In addition, horses care for their young for a long time, and both stallions and mares can share the parental responsibilities. In natural conditions youngsters generally won’t leave their family group until they are well over a year old or older, and about 25% of fillies will remain with their family group for life.

Taken together, their behavioural biology tells us that forming strong, lasting, positive social relationships is an evolutionary advantage for horses.

What does horse love look like?

Next, we have to look at how horses show ‘love’. We have previously defined love as a good, calm feeling, similar to Panksepp’s core emotion of CARE, meaning caring for someone. If we take that definition and apply it to situations of social bonding, we can identify some behaviours that are indicative of ‘love’:

approaching/seeking out each other’s company

standing close together

physical contact, for example sniffing, nuzzling each other

mutual grooming

sharing food

vocalising/”greeting” each other

But love isn’t just how we feel in the presence of someone we like, but also how we feel in their absence. A horse that is separated from a close friend or relative (for example a mare separated from her foal) will:

vocalise/call out

show stress-related behaviours

pace or weave

run and search

Can a horse love a human?

Finally, we get to the million dollar question: we’ve established that horses probably have some biological capacity for ‘love’ - but can they love us?

Horses show similar physiological and behavioural responses to humans as they do to horses. If you look at the list of ‘love’-related behaviours above, for example, you’ll see that most of them can apply to horse-human interactions, too. We know that human-directed friendly behaviours are mediated through the hormone oxytocin (Lee & Yoon, 2020; Kim et al., 2021; Nittynnen et al., 2022), which plays a role in social bonding.

One study found that horses left alone in an indoor arena were less stressed in the presence of a human (Lundberg et al., 2020), indicating that they can see us a source of safety. However, there was no difference in how the horses responded with their owners or with an unfamiliar person, which means that it may be more due to a generalised positive association with humans than ‘love’.

In fact, when it comes to the importance of familiarity to the horse-human relationship, the science is inconclusive. While a recent study found a link between the length of the relationship with a particular handler and how likely a horse was to cross an unfamiliar surface with that handler (Liermann et al., 2022), previous studies have not found any significant effect of familiarity on how horses perceive the humans they interact with (Ijichi et al., 2018; Lundberg et al., 2020; Kieson et al., 2020).

Why is that? I believe a big problem is that most of the things we do with our horses don’t mirror their social interactions, so there is little opportunity for any bonding on their terms. The few friendly behaviours horses do show, such as nuzzling or mutual grooming, are often punished because we consider them a nuisance. In fact, Nittynnen et al (2022) found that horses showed fewer and fewer friendly behaviours as their training progressed, and that their oxytocin levels went down as well. This is certainly worth a deeper reflection.

So, do horses love us?

The truth is that we don’t know. But here’s what I think, based on equine ethology and current research into horse-human relations: horses can ‘love’ us in the sense that they can feel good in our presence, seek out our company, and engage in social bonding activities with us. Anecdotally, there is evidence that horses can prefer particular people over others, too.

However, it’s important to remember that whatever capacity they have for ‘love’ is not like ours. They’re a different species and evolved to bond in a different way than we have - and that’s OK. Most importantly, we need to remember that their love is conditional on how we treat them. It is up to us to make them feel good in our presence.

Very interesting, thanks! I believe horses can care about their human if they are treated with kindness and caring, and it is mutually beneficial for humans to be kind to each other as well as to all animals. My ‘one in a million’ mare came to me at age three and was part of my life until she was forty. She taught me a lot and enriched my life as we learned to communicate with each other as much as possible in non-verbal but meaningful ways.

I've seen my relationship with my horse changed when I started to respond to every nosing behaviour he offered. Just offering my hand for him to sniff, playing slowly with his mouth or even just interrupting what I was doing to acknowledge that he was reaching out.

Now, he's communicating sooo much more and is much more chilled at the same time. I even got groomed back a few times when I was scratching an itchy spot. Of course we have to figure out how to make this work in a horse-to-human way. I'm really sad to see that it's been studied how these behaviours disappear in relationship to time spent in training.