Being able to recognise one’s own reflection in a mirror is considered the ultimate proof of self-awareness. So far, only very few species apart from our own have passed the mirror test: chimpanzees, elephants, dolphins, magpies and, in a plot twist that surprised every biologist on the planet, the cleaner wrasse fish.

We may now be able to add horses to the list, thanks to the research efforts of Italian ethologist Paolo Baragli and his team. They tested 11 horses in a four-day mirror test and discovered that some of the horses seemed to understand that they were looking at their own reflections.

The principle behind the mirror test is simple: if an animal understands that it sees itself in the mirror – rather than thinking the reflection is just another individual of the same species – then it must be aware of its own existence. But the execution of the mirror test is a bit more complicated. When testing their horses, Baragli and his team divided the experiment into four phases:

The horses got to explore a covered mirror.

The horses got to explore an uncovered mirror.

An invisible mark was painted on the horses’ cheeks.

A visible mark was painted on the horses’ cheeks.

As mirrors don’t exist in nature, horses don’t understand them the way they understand rocks or tree branches. When first exposed to a mirror, they need some time to figure out what it is. By looking at it and sniffing it they are given the chance to realise that they’re not just looking at another horse.

That’s what the first two steps were for. The experimenters wanted to see if the horses behaved differently in front of the uncovered mirror compared to the covered one. Specifically, they were looking for so-called contingency behaviours. These are repetitive behaviours directed at the mirror, for example looking behind the mirror, sticking their tongue out, moving their head up and down, or doing a peek-a-boo behaviour where they move their head out of sight of the mirror and then back again. If the horses do them more frequently in the presence of the uncovered mirror, it indicates that they are experimenting to see if their reflection will behave the same way they do.

According to Baragli and his team, the horses in the study passed this first part of the mirror test:

Nine out of the eleven horses performed the peek-a-boo behaviour when the mirror was uncovered. No horses performed it when the mirror was covered.

The horses moved their heads more in front of the uncovered mirror compared to the covered mirror.

More horses looked behind the uncovered mirror compared to the covered one.

No horses stuck their tongues out when the mirror was covered, but one horse stuck her tongue out ten times when the mirror was uncovered.

Does this mean that the horses showed signs of self-recognition and were experimenting to see if their reflections would behave the same way they did? Possibly. Here’s where interpreting science becomes difficult. All the behaviours above, except for looking behind the mirror, are calming signals that horses exhibit in mildly stressful situations. It’s possible that they were simply worried by the unfamiliar object rather than consciously trying to understand it. If they thought their mirror image was another horse, the signals may have been attempts to communicate with it.

Once the horses passed the first two phases, the horses were subjected to a mark test. First, an invisible mark was painted on their cheeks, and they were placed in front of the mirror. After that, the procedure was repeated with a visible mark in the same spots. The experimenters recorded the horses’ behaviours in front of the mirror in both situations.

For an animal to pass the mark test, it needs to show self-directed behaviours indicative of wanting to remove the visible mark, but not the invisible one. The horses in Baragli’s experiment did:

Nine out of eleven horses scratched their faces when the mark was visible, and only five out of eleven horses scratched their faces when the mark was invisible.

Four horses spent significantly more time scratching their faces when the mark was visible compared to when the mark was invisible.

Are there other explanations for these results?

Yes. Face scratching is a common displacement behaviour that horses show during behavioural conflict and could be related to stress rather than self-recognition. It would be interesting to know whether any of the horses scratched their faces in the first two test phases – if it was indeed a stress-related behaviour it would likely show up in the earlier phases, too.

Studying animal cognition is difficult, because we can’t ask them how much they understand or whether they are aware of their own existence. Scientists do their best to design experiments that can help bring us closer to the truth, and the mirror test is one such experiment. But it’s not without its limitations.

Interpreting behaviour is tricky, as we’ve seen, and we can never know for certain whether an animal is trying to remove a mark from its body or just behaving in a way that looks like it is. And some animals may not even care whether they have a mark on their body. Horses, for example, roll in mud all the time when given the opportunity. Why would they want to remove a stain from their cheek when one of their main physical maintenance behaviours is to make themselves dirty?

Furthermore, the mirror test is biased towards animals that use vision to identify individuals, such as humans and chimpanzees. But there are plenty of other senses in the natural world. Lately, adaptations of the mirror test have been made to better suit animals that rely on olfactory cues to recognize conspecifics, such as scent markings. Dogs, for example, will spend more time sniffing a sample of their own urine if a strange odor is mixed in – a sign that they recognize their own scent and pay attention when something changes about their olfactory “appearance”.

So, what’s the bottom line here? Are horses self-aware?

Of course they are – to some extent. While the results of Baragli’s study aren’t conclusive enough to claim that horses recognize themselves in a mirror, horses do show cognitive processes indicative of some level of understanding that they are different from other members of their species. They recognize other individuals, for example, and form strong bonds with each other. They gather information about other individuals by sniffing poop piles, and stallions will defecate on top of other stallions’ piles.

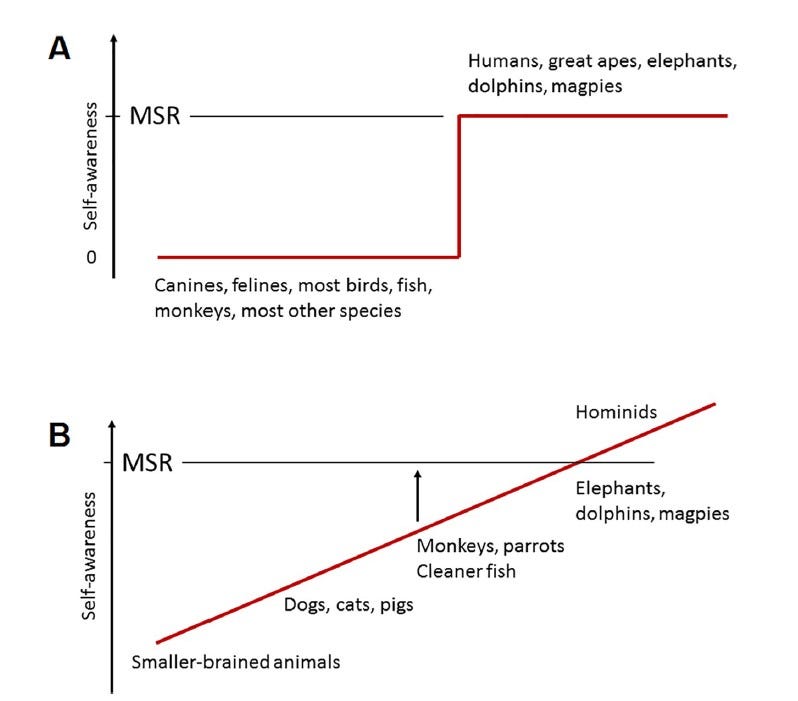

Self-awareness isn’t all-or-nothing. It’s not a trait that appeared spontaneously during evolution in a limited number of species but rather a cognitive process that is adaptive and evolving. There are likely different levels of self-awareness, from the lowest forms in smaller-brained animals to the highest levels in humans and chimpanzees who recognize their own reflections in a mirror (although the age at which a human child starts to display mirror self-recognition varies!).

Like intelligence, each species has the exact kind of self-awareness that it needs to survive in its specific habitat. Every living being needs some sort of understanding of its own relationship with the surrounding environment.

This is called the gradualist approach to self-awareness, and it has been championed by scientist like Frans de Waal, one of the world’s leading experts on animal cognition. Here is a graph from his 2019 paper “Fish, mirrors and a gradualist perspective on self-awareness” that I think does a great job of illustrating this view.

So where would horses fit on this graph? Maybe with dogs, cats, and pigs.

If you liked this post, please consider sharing it with a friend who might be interested in subscribing!